Redo Parathyroid Surgery

On occasions it is sometimes necessary to perform another parathyroid operation, which is known as recurrent or redo parathyroid surgery.

Causes of failed parathyroid surgery

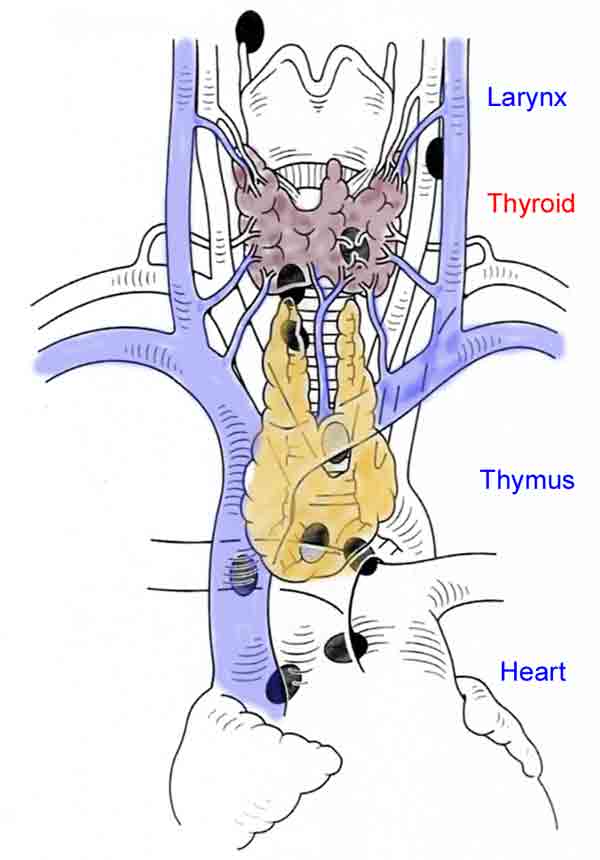

Fig.1: Diagram of ectopic locations of parathyroidsSo how can parathyroid surgery fail to fix the problem of hypercalcaemia (high blood calcium)?

Fig.1: Diagram of ectopic locations of parathyroidsSo how can parathyroid surgery fail to fix the problem of hypercalcaemia (high blood calcium)?

This can occur in some patients if the parathyroid is unable to be found at the first operation (persistent disease) or if there is a second gland that develops disease later (recurrent disease). Recurrent disease is generally defined as occurring more than 6 months after the initial operation, while persistent disease occurs less than six months after the first operation, and usually, in fact, is evident straight afterwards, when the calcium fails to return to normal.

Persistence accounts for 80-90% of reoperations, and is usually due to inadequate surgery, most commonly failure to identify and remove the parathyroid tumour or incomplete removal of hyperplastic tissue in the case of multiglandular disease.

Recurrent disease is usually due to the underlying disease process, most commonly caused by the regrowth of abnormal parathyroid tissue in multiglandular hyperplasia.

The common causes of failed parathyroid surgery are:

- persistent disease

- ectopic position (Fig. 1)

- unexpected double gland disease

- unsuspected hyperplasia

- more than four glands

- inexperienced surgeon - recurrent disease

- hyperplasia treated by subtotal parathyroidectomy

- recurrent or metastatic parathyroid cancer

- parathyromatosis

The risk of persistent disease is less than 2 in 100, provided there has been good localisation. Persistent disease can occur when the overactive gland is ectopic (in an unusual position), such as down in the chest or within the thyroid.

It is also possible to have more than one gland affected by disease, but only show up as single-gland disease on the preoperative investigations (double adenoma). On occasion, the surgeon can be very satisfied having located a large gland at operation, only to find postoperatively that the calcium remains stubbornly high, because of a second much smaller, but active gland.

In addition, some patients may have unsuspected hyperplasia, now made more difficult to diagnose at operation with the advent of minimally-invasive parathyroidectomy (MIP), when only a single side is explored. It is also possible for a patient to have more than four glands (see webpage on Anatomy), with the tumour in the fifth (or more) gland, and therefore not found as it is in an ectopic position.

Patients with hyperplasia, secondary to renal disease for example, who opt for less than total parathyroidectomy also must be warned of the risk of recurrence years after initial surgery. Recurrent disease can also be caused by parathyromatosis, where a parathyroid adenoma has been accidentally 'seeded' into the neck at the first operation and regrown later.

Problem Solving Strategies to Prevent Failure at Initial Surgery

When parathyroid exploration is undertaken, in most cases the search for abnormal parathyroids is relatively straightforward, but about 20% of cases can present problems. It is important to have a strategy to follow, and remember the following points, which may help in difficult cases:

1. The parathyroids are usually symmetrical on either side of the neck

If a normal parathyroid is found, mark it immediately with a ligaclip as it can be surprisingly elusive when you try to find it again. Once it has been marked, and therefore knowing where to look on the other side, it is often much easier to locate the opposite parathyroid. Remember that a huge parathyroid tumour may be mistaken for a thyroid nodule, and vice versa.

2. Inconsistent with imaging

When the parathyroid findings are not consistent with the imaging, the localisation study might be wrong, or has been misinterpreted. For example, a tumour in a descended superior gland may lie behind a normal inferior gland.

The strategy would be to explore the remainder of that side through the same (or a slightly enlarged) incision. If there is still no adenoma evident, then the operation should be converted to an open 4-gland exploration by extending the incision to the other side.

if the adenoma is found at a different site to that suggested by imaging, continue the exploration of that side to find a normal gland and exclude hyperplasia, but don't explore the other side at this stage. It must be borne in mind however that unfortunately double adenomas are more likely to be on opposite sides of the neck than on the same side.

3. Double adenoma or Hyperplasia?

If two enlarged parathyroid glands have been located, this raises the possibility of hyperplasia, so all 4 glands should be explored.

4. Missing parathyroids

There is an adage in parathyroid surgery: 'When the upper gland is missing, look low, and if the lower gland is missing, look high'. But it is important to remember that it is not always possible to be sure whether an upper or lower parathyroid is missing. The search should be undertaken in known embryological sites in order of prevalence.

When three normal or hyperplastic glands have been found and an upper parathyroid is missing, think POSTERIOR. Look behind the oesophagus and pharynx down to the posterior superior mediastinum. It is likely to be in the tracheo-oesophageal groove or retro-oesophagus, or possibly the carotid sheath. Explore also in the carotid sheath, and up around the superior thyroid pedicle up as far as the carotid artery bifurcation, and consider whether the parathyroid may be inside the thyroid lobe, in which case a lobectomy may solve the problem.

If the lower parathyroid is missing it is most likely to be found in the thymus, within the thyroid or possibly undescended, hence the advice to 'look high', around the submandibular gland. Because of the embryological origin of the lower glands, they may be found in the thymus, so if the gland still cannot be found perform a cervical thymectomy on the side of the missing parathyroid.  Fig.2: Cervical thymectomy (left) and parathyroid tumour within the removed thymus (right)Cervical thymectomy is easy to do with virtually no complications. Identify the thymus at the lower pole of the thyroid; thymic tissue has a distinct structure to it, unlike fat. Separate the thymus from the thyroid and divide the thyro-thymic ligament, pick up the upper end of the thymus and pull it by continual traction out of the chest (Fig. 2).

Fig.2: Cervical thymectomy (left) and parathyroid tumour within the removed thymus (right)Cervical thymectomy is easy to do with virtually no complications. Identify the thymus at the lower pole of the thyroid; thymic tissue has a distinct structure to it, unlike fat. Separate the thymus from the thyroid and divide the thyro-thymic ligament, pick up the upper end of the thymus and pull it by continual traction out of the chest (Fig. 2).

As the thymus is delivered the thymic vein appears posteriorly as a single vessel and must be divided. Thymectomy should be virtually bloodless and often produces the missing gland within its substance.

If that fails to reveal the gland, then a hemithyroidectomy may be performed, exploration of the carotid sheath along its length, and finally exploration around the submandibular gland.

In parathyroid hyperplasia, particularly in renal patients, it is not uncommon for extra parathyroids or at least parathyroid tissue to be found in the thymus. In view of this it is best to perform bilateral excision of both thymic lobes even though four glands may have already been found.

Persistent & Recurrent Disease

With persistent disease, it is relatively simple to diagnose, as the calcium fails to return to normal, or normalises only for a short period before rising again. Recurrent disease usually presents in a similar way to most cases of primary hyperparathyroidism, although the cause may be more obvious compared with a patient with persistent disease. In the case of a renal patient with secondary hyperparathyroidism for example, if there has only been a subtotal parathyroidectomy, the recurrence is likely to be in the retained gland.

In both cases further investigations will be needed to locate the missing gland, or the extra gland, causing the calcium to stay elevated.

Conservative management

It is important to remember that it may be possible to manage the problem more conservatively, without resorting to another operation, if the symptoms are relatively few and the calcium is only mildly elevated. If the scans remain stubbornly negative, but the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism is firm, it may be possible to manage the patient conservatively and not resort to a potential failed operation.

If the patient is relatively asymptomatic, with minimal bone disease and no history of renal stones, then minimal harm is likely if the surgical option is delayed for 12 months and the scans then repeated. 43% of patients with an initial negative Sestamibi scan will be positive when the scan is repeated at 12 months, allowing the possibility of MIP.

The reasons for this are not clear, but may be related to growth in the size of the adenoma, random variation in the activity and secretion rate of the adenoma, or possibly undertaking the scan in a more experienced centre.

Initial steps

The best way of preventing failure at parathyroid surgery is to have good localisation studies prior to any exploration of the neck. It is important to confirm the diagnosis and the indications for surgery, to satisfy yourself that exploration is warranted, and review the family history (to exclude FHH).

In all cases, the initial approach should follow a standard pattern:

- reconfirm the diagnosis with blood tests

- exclude other causes, like renal insufficiency, vitamin D deficiency and FHH

- review the imaging personally

- review the operative notes of the primary surgeon to find out what was done, and be sceptical about labels given by the previous surgeon

- review the pathology report to find out what was found; were any glands removed or any biopsied?

Investigation

In reinvestigating the patient with persistent or recurrent disease, it would be best to begin with either a review of the original scans or a repeat Sestamibi and ultrasound scan, preferably in a high-volume experienced centre.

It is important that the surgeon reviews the localisation studies personally, as radiologists are less likely to call a scan positive than a surgeon, who can recognise subtle assymetry in the anatomy. The Sestamibi scan technique may also be inadequate, for example without SPECT views, requiring it to be repeated.

If the ultrasound and Sestamibi scans are still negative, then consider using 4D-CT to localise the adenoma, which has high sensitivity and may allow a MIP procedure to be done, rather than resorting to a four-gland exploration of the neck. MRI, or [11C] methionine PET-CT are other possibilities, but sometimes more invasive methods such as selective venous PTH sampling, with or without angiography, may be required.

1. 4D-CT

A new method of localising parathyroid tumours has recently been developed, called 4-dimensional computed tomography (4D-CT). The name of the technique is derived from 3-dimensional CT scanning with the added dimension of time, looking at the changes in perfusion of contrast through a parathyroid tumour. CT has the advantage that it will visualise ectopic parathyroids in the anterior mediastinum, where ultrasound cannot see.

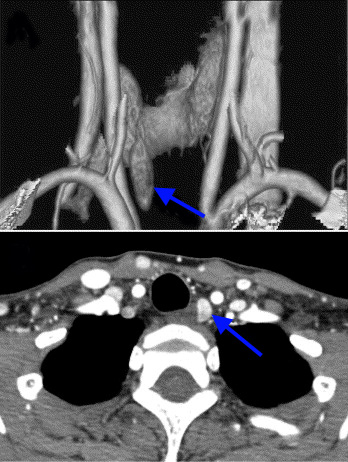

Fig.3: 4D-CT scan of L upper parathyroid tumour, with 3D reconstruction (above) and cross-section (below)

Fig.3: 4D-CT scan of L upper parathyroid tumour, with 3D reconstruction (above) and cross-section (below)

4D-CT produces very detailed, multiplanar images of the neck and allows the visualization of differences in the perfusion characteristics of hyperfunctioning parathyroid glands (ie, rapid uptake and washout), compared with normal parathyroid glands and other structures in the neck (Fig. 3).

The images that are generated by 4D-CT provide both anatomical and functional information (based on the changes in perfusion) in a single study, unlike the conventional two study (US & Sestamibi) technique.

There are downsides to the technique however, as firstly it is not widely available, requiring a particular expertise. Secondly, there is some concern that the radiation dose to the thyroid appears to be more than 50 times higher than conventional techniques, raising the possibility of 4D-CT-related thyroid cancers developing in the future.

This may be ameliorated in the future by the use of the latest low-dose CT scanners, which considerably decrease the exposure to radiation. Nevertheless it is probably prudent to avoid the use of 4D-CT in younger patients.

In view of these downsides, 4D-CT, or thin-slice high resolution conventional CT is generally only employed to find a 'lost' gland after a failed exploration for a parathyroid tumour. It is unusual to use CT as a first line investigation in the unexplored neck.

2. Selective venous sampling and angiography

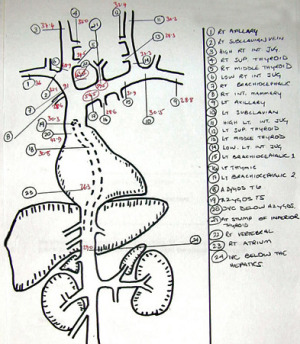

Fig.4: Venous sampling map to identify greatest source of PTH and likely site of a tumourIn the patient who has had a previous failed exploration, perhaps due to a mediastinal adenoma, more invasive tests may be needed in addition to sestamibi scan and ultrasound, or 4D-CT.

Fig.4: Venous sampling map to identify greatest source of PTH and likely site of a tumourIn the patient who has had a previous failed exploration, perhaps due to a mediastinal adenoma, more invasive tests may be needed in addition to sestamibi scan and ultrasound, or 4D-CT.

Selective venous sampling is a useful technique requiring the passage of catheters from the groin into the arteries and veins of the neck.

Multiple samples of venous blood can be taken from around the neck and upper mediastinum, allowing the identification of the greatest source of PTH, and thus the likely site of a parathyroid tumour. A map of the results can then be produced to guide the surgeon in a subsequent exploration (Fig. 4).

Selective angiography can also be added, looking for the characteristic 'blush' of contrast which identifies the abnormal parathyroid tissue.

Selective angiography will usually identify the missed gland, with a sensitivity of 90-95%, especially when combined with venous sampling for parathyroid hormone assay.

Almost all enlarged glands are hypervascular, with a distinctive angiographic “blush”, resulting in a low false positive rate.

Redo surgery

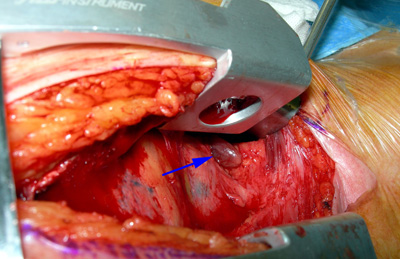

Fig.5: Re-exploration surgery for a missed parathyroid tumourReoperative parathyroid surgery is challenging; it is associated with higher levels of recurrent laryngeal nerve (voicebox nerve) palsy (4-10%) and hypoparathyroidism (low blood calcium) (10-20%).

Fig.5: Re-exploration surgery for a missed parathyroid tumourReoperative parathyroid surgery is challenging; it is associated with higher levels of recurrent laryngeal nerve (voicebox nerve) palsy (4-10%) and hypoparathyroidism (low blood calcium) (10-20%).

Once the abnormal gland has been identified at imaging studies, only then can re-exploration of the neck be contemplated (Fig. 5). It is important at this point to decide if reexploration is actually warranted. This is appropriate with well-localised disease or if severe symptoms or severe hypercalcaemia (>2.9mmol/l) is present. If not, then a wait and watch approach might be more prudent.

Over two-thirds of patients with recurrent or persistent disease have a solitary enlarged gland. In one large series of reoperations, abnormal glands were found in the usual positions in 70%, and in ectopic positions in only 25%; extra glands were the cause in only 0.7%.

Redo parathyroid surgery generally involves a focused approach to a single gland, which is in, or accessible from, the neck in more than 90% of cases, but may be in the mediastinum, requiring sternal split (manubriotomy) for access. Biopsy and/or removal of normal glands should be avoided.

When a patient has had a full open neck exploration previously, scarring can make the usual approach more difficult and dangerous. When re-exploring for a missed or recurrent parathyroid it is best to use the "back-door" approach (the usual approach in minimally invasive surgery). This is not so much of a problem with previous MIP surgery, as exploration of the other side should be in virgin undisturbed territory.

This approach allows early identification of the RLN which is usually found in the space between the carotid artery laterally and the trachea medially. The nerve and its branches should be traced through the operative field before a search is made for the missing parathyroid tumour or tumours. The use of the intraoperative nerve monitor is vital to help identification and to protect it from damage.

When the nerve on the right side is missing it is important to remember that it may be a non-recurrent laryngeal nerve. The nerve will be found high up in the neck and its course near the thyroid is similar to the inferior thyroid artery.

Exploration of the mediastinum

Fig.6: Manubriotomy revealing an upper mediastnal parathyroid tumourProvided there is good prior localisation, exploration of the mediastinum through a partial upper sternal split (manubriotomy) will usually allow an ectopic tumour to be removed successfully (Fig. 6).

Fig.6: Manubriotomy revealing an upper mediastnal parathyroid tumourProvided there is good prior localisation, exploration of the mediastinum through a partial upper sternal split (manubriotomy) will usually allow an ectopic tumour to be removed successfully (Fig. 6).

This should only be done at first exploration if the tumour has been definitely identified to be lying in the chest, but remember that many will be in the thymus and may be able to be delivered from the neck incision.

In the very rare case that this does not reveal the offending tumour in the anterior mediastinum, consider dividing the left innominate vein and dissecting down between the pulmonary artery and aortic arch in the aorto-pulmonary window.

CT imaging will have identified this before you ever get into the chest however, so you and the anaesthetist should be well prepared for the possibility.