Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1 syndrome)

MEN1 syndrome is caused by a mutation of the MENIN gene on chromosome 11 in more than 90% of cases. More than a thousand mutations have been describedin chromosome 11q13. MENIN is a tumour suppressor gene, so that mutations tend to turn off the gene, resulting in tumour development.

The prevalence of MEN1 is about 0.2-2 per 100,000 people (although in Tasmania this rate rises to 24 per 100,000), with a female to male ratio of roughly 1:1.

Nearly 80% of MEN1 patients will have developed at least one of the specific endocrine tumours by the age of 50, and 43% by the age of 20, although cases have been recorded in even younger patients. The condition varies greatly even within families; not everyone will have the same tumours and they will not occur at the same age; also, not all MEN1 patients will have all of the tumours.

Clinical Features

MEN1 syndrome is characterised by the coexistence of a variety of endocrine diseases, with more detail on some conditions found on their own webpages by following the links:

- hyperparathyroidism

- affects more than 40% by age of 20 years, near 100% by age 50 years

- most have a multiglandular involvement, which can be assymetrical, with not very high PTH levels

- they are generally diagnosed on biochemical screening for raised calcium, rather than with the classical symptoms - enteropancreatic tumours

- these occur in up to 80%, with often multicentric tumours and possible malignant transformation, making surgical cure less likely in MEN1 patients

- most are non-functional, occurring in 80-100% (although actually these generally produce pancreatic polypeptide, which has no clinical symptoms)

- of the functional tumours, 40% develop gastrinomas manifesting as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, which is characterised by increased gastrin production, leading to raised gastric acid levels and therefore peptic ulceration and diarrhoea

-these gastrinomas are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in MEN1 syndrome

- 10-30% develop insulinomas causing excessive insulin production and therefore all the symptoms of low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia)

- other functional tumours like glucagonomas and VIPomas develop in less than 5% of MEN1 patients - pituitary tumours

- occur in 30-40% of MEN1 patients, usually as prolactinomas (60% of MEN1-associated pituitary tumours) which in women causes production of milk (galactorrhoea) and absence of periods (amenorrhoea), while in men it causes impotence and infertility

- growth hormone producing tumours (25%)

- ACTH-secreting tumours (3%)

- non-functional tumours (12%) - other tumours

- carcinoid tumours are found in thymus (men), which tend to be malignant and highly lethal; and in the lung bronchus (women), which tend to be benign

- cutaneous tumours such as angiofibromas, collagenomas and lipomas

- adrenocortical tumours occur in 20-40%, usually benign and non-functional

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of MEN1 syndrome is suspected when the specific cluster of endocrine tumours occurs, usually but not always in a patient with a known family history of MEN syndrome. Investigations are geared to cover the most likely types and sites of tumours:

- hyperparathyroidism

- screening with blood calcium and PTH measurement annually from age 10

- imaging is usually not needed as bilateral neck exploration will be required - enteropancreatic tumours

- screening by annual fasting gastrin, insulin, glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide levels

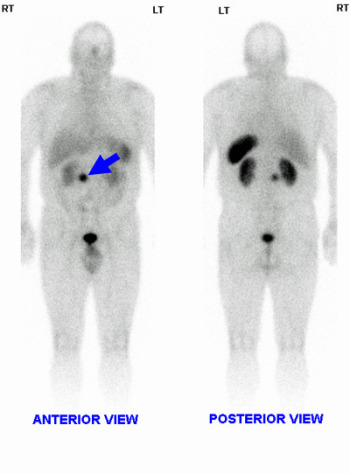

- endoscopic ultrasound is very effective in localising pancreatic tumours, with confirmation by octreotide scintigraphy (Fig. 1) Fig.1: Octreotide scan showing gastrinoma (arrow)

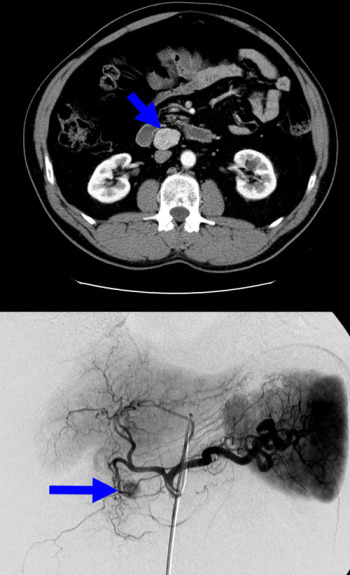

Fig.1: Octreotide scan showing gastrinoma (arrow) Fig. 2: CT of gastrinoma (above); angiography of insulinoma in head of pancreas (below)

Fig. 2: CT of gastrinoma (above); angiography of insulinoma in head of pancreas (below)

- CT or MRI scanning will find anatomically larger tumours, while small tumours may require angiography and selective venous sampling (with calcium injection which stimulates hormone secretion) to find the tumour (Fig. 2) - pituitary tumours

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with attention to the pituitary fossa region, is the best test if a pituitary tumour is suspected on biochemical evidence

Treatment

1. Medical treatments

There are a number of medical therapies that can control symptoms for extended periods in order to avoid what can be difficult surgery with high recurrence rates.

MEN1-associated tumours are often multicentric, making surgical cure unlikely. However, if surgery is possible and the tumour is well localised then operative removal is generally the best option.

- Hyperparathyroidism

- surgery is the treatment of choice (see below)

- for patients who cannot undergo surgery, bisphosphonates and potentially calcimimetics may be useful - Gastrinoma

- symptoms can be well controlled with proton pump inhibitors which inhibit acid hypersecretion

- metastatic gastrinoma may be treated with streptozocin and doxorubicin; octreotide might decrease tumor progression - Insulinoma & other pancreatic islet cell tumours

- surgical removal is the treatment of choice

- for unresectable tumours treat with diazoxide and long-acting somatostatin analogues - Prolactinomas

- can be treated with bromocriptine or other dopamine agonists

2. Surgical Treatment

In general, surgery is the first and best choice for controlling symptoms that are medically intractable and to prevent metastases of enteropancreatic neoplasms.

- Hyperparathyroidism

- parathyroidectomy is the treatment of choice

- as patients have multiglandular disease, a full neck exploration is required with either subtotal parathyroidectomy or total parathyroidectomy and autotransplantation; thymectomy must be included

- there has been some recent work at Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney suggesting minimally invasive surgery might be appropriate if an abnormal gland can be identified preoperatively, removing the abnormal gland, plus the normal parathyroid and thymus on the same side

- there is a lower success rate in MEN1 due to the multiglandular disease: 75% have a normal calcium after the operation, 10-25% are hypoparathyroid (lowered parathyroid function) resulting in the need for calcium and vitamin D replacements

- 50% become hypercalcaemic again within 10 years due to any remaining tissue quickly regenerating, thus total parathyroidectomy without autotransplantation may be a better option in some patients, with permanent calcium and vitamin D replacement - Gastrinoma

- the role of surgery in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome with MEN1 is controversial as cure is only achieved in 10-15% of cases due to the often multicentric tumours

- surgery is indicated if tumour is well localised and there are no distant metastases; large tumours should also be removed to reduce the frequency of liver metastasis

- local tumour excision is preferred, with larger tumours of the pancreatic body or tail removed by distal pancreatectomy - Insulinoma & glucagonoma

- these are usually single large tumours that can be enucleated at laparoscopy or open surgery; intraoperative ultrasound is very helpful at tumour identification

- they may be multicentric and small, and in some MEN1 cases the lesion detected radiologically may not actually be the one causing hypoglycemia, hence the need for venous sampling to localise the insulin secretion - Pituitary tumours

- can be removed by transsphenoidal pituitary surgery (via the nose)

- prolactinomas can be large and multicentric and the recurrence rate is high

Prognosis

Improved knowledge of MEN1-associated clinical manifestations, early diagnosis of MEN1-associated tumours, presymptomatic screening of at-risk children, and treatment of the metabolic complications of MEN1 have virtually eliminated Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES) and/or complicated hyperparathyroidism as causes of death, and decreased the morbidity and mortality associated with MEN1-related tumours.

Despite treatment, there is a 50% risk of mortality by the age of 50 years. Half of these patients die as a consequence of a malignant tumour, usually in the gut or pancreas, as well as thymic carcinoids. The treatment of hyperparathyroidism does not alter mortality.